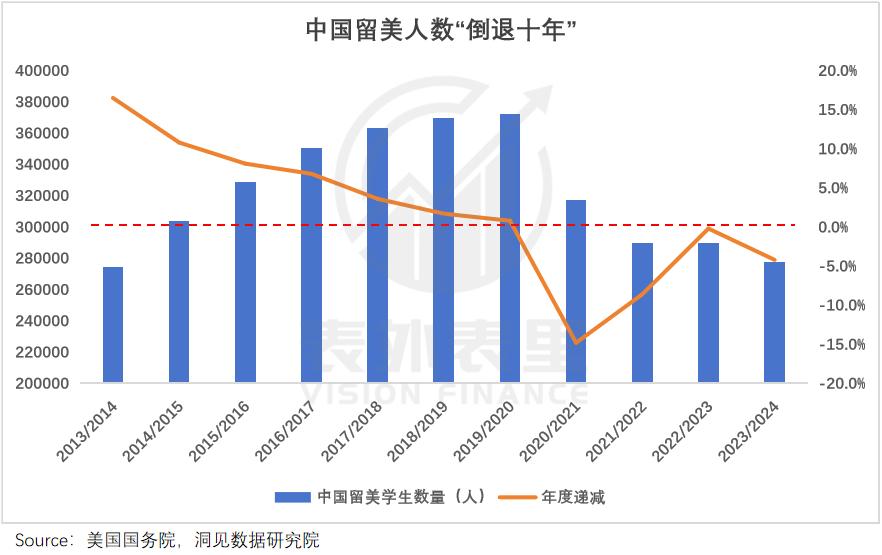

Positive Comments: From Disenchantment with the “American Dream” to Rational Choices, the Awakening of the Overseas Student Group and the Two – way Attraction with Domestic Development

In recent years, the phenomenon of Chinese overseas students “fleeing the United States” not only reflects the shift in individual choices but also the collective awakening of the entire overseas student group from blindly chasing the “American Dream” to rationally evaluating the domestic and international environments. This transformation, which is both a clear – eyed recognition of the social reality in the United States and an active embrace of domestic development opportunities, holds profound significance in the current era.

Firstly, the process of disenchantment among overseas students essentially represents a return of educational choices from “symbolization” to “practicality”. As mentioned in the news, in the past, the enthusiasm of parents and students for American education largely stemmed from the filter of the “theory of American invincibility” – Ivy League degrees, high – paying jobs, and a free lifestyle were distorted into “tickets” for social class advancement. However, reality shattered this illusion: the ever – changing visa policies, the tightening job market, and the spread of identity anxiety have sharply increased the cost of realizing the “American Dream”. For example, overseas students like Daxiong found that behind the so – called “liberal education” in American universities lies a more implicit form of competition – not only do they have to compete for high GPAs, but also for internship and project experience; and the so – called “world – class resources” are actually far less accessible under visa restrictions and major reviews. This disenchantment has brought the decision – making on overseas study back to its essence: the core of education is the improvement of abilities and career development, rather than simply “gilding” or using it as a “springboard for immigration”.

Secondly, the certainty and opportunities in domestic development have become the key driving force for overseas students to “want to return home”. As Yuyang mentioned in the news, “The gap between the domestic and international situations is not as significant as before, and in some aspects, we are even more advanced.” This judgment is not baseless. In recent years, China’s rapid rise in fields such as the digital economy, new energy, and artificial intelligence has provided vast career opportunities for highly educated talents. For instance, the R & D investment of domestic internet giants and the innovation vitality of emerging technology companies are no less than their American counterparts; and the policy orientation of “new – quality productivity” has enabled overseas students with technical backgrounds to see opportunities for the integration of industry, academia, and research. In addition, the optimization of domestic policies for returnees (such as settlement subsidies and entrepreneurship support) and the strengthening of family emotional bonds (in the news, Yuyang was opposed by his elders for choosing to study in Hong Kong and Macau because it was “close to home”, but he finally made a rational decision) have made returning home no longer a “second – best choice” but a decision to “actively embrace opportunities”.

More notably, this group – wide shift is promoting the global re – allocation of educational resources. In the past, the United States, relying on its cluster of top – tier universities and favorable immigration policies, had long monopolized high – quality Chinese overseas student resources. Now, with the increasing educational investment in regions such as the United Kingdom, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau (e.g., the rising QS rankings of Hong Kong universities, Singapore’s launch of the “Global Talent Visa”) and the remarkable achievements of China’s “Double First – Class” initiative (five mainland universities made it onto the 2025 QS rankings), overseas students have more diverse choices. This not only reduces the risk of individual impact caused by policy changes in a single country but also forces the global education market to improve its service quality and form a more positive competitive ecosystem.

Negative Comments: The Intensified Risk of Overseas Study Investment and the Temporary Setback in Educational Exchanges

Although the “trend of overseas students returning home” is the result of rational choices, the problems behind it also deserve our vigilance: the imbalance between the cost and return of overseas study, the obstruction of individual development paths, and the temporary setback in Sino – US educational exchanges may have long – term impacts on individuals, families, and even the country.

Firstly, middle – class families’ “gambles on overseas study” face higher risks. As mentioned in the news, “The proportion of overseas students whose parents’ professional backgrounds are ‘ordinary employees’ has increased significantly.” Overseas study has shifted from an “elite choice” to a “mass consumption”, but the logic of “recouping the investment” is gradually failing. Take Daxiong as an example. His four – year undergraduate study in the United States cost his family over 2 million yuan. He originally expected to “recoup the investment in three to five years”, but in reality, due to “layoffs in large companies” and “competition from experienced candidates for jobs”, the return period for his overseas study investment has been infinitely extended. More seriously, some families “sell their cars and houses” to support their children’s overseas study. Once they encounter black – swan events such as visa cancellation or employment failure (e.g., Judy’s science and engineering friends were advised to drop out by their tutors, and Lily failed to win the H – 1B visa lottery), it may lead to a family financial crisis. This overseas study model of “high investment, high risk, and low certainty” is eroding the educational investment confidence of some families.

Secondly, the “identity anxiety” in individual development may affect long – term competitiveness. Studying in the United States is supposed to be a process of cultivating a global perspective and cross – cultural abilities, but the real experiences of overseas students in the news are filled with a sense of “marginality”: although they have passed the language barrier, social isolation due to “unable to change their skin color” (e.g., Lucy was marginalized at a party for not drinking), implicit discrimination in the workplace (Judy experienced “delayed service” and “anti – Asian emails”), and the “precariousness” caused by policy changes (visa revocations and fund cuts during the Trump administration) have left many overseas students in a dilemma of “unable to integrate into the United States and unable to return to their hometowns”. This anxiety not only consumes psychological energy but may also weaken the accumulation of their professional abilities – for example, constantly changing internships and sending out numerous resumes to deal with identity issues, they are unable to delve deeply into a particular field, and ultimately “try to please everyone but end up getting nowhere”.

In addition, the cooling of Sino – US educational exchanges may affect technological innovation and cultural mutual learning. For a long time, Chinese overseas students have been an important bridge for Sino – US academic cooperation: they participate in cutting – edge research at American universities (such as in artificial intelligence and aerospace) and some of them return to China to promote technology transfer after graduation. However, as mentioned in the news, overseas students in “sensitive majors” are restricted from participating in projects, and tutors are advising students to drop out due to review pressure. This “technological decoupling” is cutting off the capillary vessels of academic exchanges. If this trend continues, it may not only slow down China’s technological catch – up in some fields but also cause American universities to lose high – quality students (Chinese students used to be an important source of tuition fees for American universities), resulting in a “lose – lose” situation.

Advice for Entrepreneurs: Seize the Opportunity of the Return of Overseas Talents and Build an Open and Inclusive Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

Facing the “trend of overseas students returning home”, entrepreneurs should actively seize this talent dividend and at the same time pay attention to their pain points and provide a suitable development environment for them. The following are some specific suggestions:

-

Precisely Meet Demands and Provide Differentiated Support: Overseas students have the dual advantages of “international perspective + professional background”, but they also face problems such as “difficulty in adapting to the domestic workplace” and “asymmetry of policy information”. Entrepreneurs can cooperate with the government and universities to establish a “service platform for returnee talents”, providing services such as policy interpretation (e.g., settlement and tax incentives), industry resource matching (e.g., cooperation between upstream and downstream of the industrial chain), and cultural adaptation training (e.g., domestic workplace rules and interpersonal relationship handling). For example, for overseas students in technical fields, an “industry – academia – research transformation center” can be established to help them combine their overseas research results with domestic industrial needs; for those in liberal arts fields, entrepreneurship incubation support in areas such as new media and cross – border e – commerce can be provided.

-

Value Cross – cultural Abilities and Build an Inclusive Team: The experience of being “marginalized” among overseas students makes them more proficient in cross – cultural communication, but cultural differences may also cause frictions within the team. Entrepreneurs should encourage the team to be inclusive of diverse cultures. For example, “cross – cultural workshops” can be organized to help local employees understand the thinking patterns of overseas students, and at the same time, guide overseas students to actively learn domestic market rules (such as user habits and policy orientations). In addition, an “international project team” can be set up, allowing overseas students to lead cross – border business (such as overseas market expansion and international cooperation negotiations) to give full play to their language and cultural advantages.

-

Keep an Eye on Policy Dynamics and Reduce Uncertainty Risks: One of the major concerns for overseas students returning to China to start businesses is policy changes (such as visa, tax, and industry access policies). Entrepreneurs can establish a “policy research group” to keep track of relevant domestic and international policies in a timely manner (such as the United States’ restrictions on Chinese students and the updates of China’s “Entrepreneurship Program for Overseas Returnees”) and provide risk warnings for overseas students in the team. For example, if a certain field may face US technology blockade, the R & D direction can be adjusted in advance to focus on domestic alternative technologies that are already mature; if a certain region in China launches a “subsidy for overseas students’ entrepreneurship”, targeted arrangements can be made for implementation.

-

Strengthen Emotional Bonds and Build Long – term Trust: The phenomenon of overseas students “not returning to China for four or five years” in the news reflects their emotional needs for family and native culture. Entrepreneurs can help overseas students rebuild emotional bonds through activities such as “family days” and “local cultural events”; at the same time, enhance their sense of belonging to the enterprise through “long – term equity incentives” and “career development path planning”. For example, overseas students can be given the opportunity to rotate between domestic and overseas positions, which can not only meet their need for a global perspective but also deepen their understanding of the domestic market.

In conclusion, the “trend of overseas students returning home” is both the result of rational choices by individuals and a microcosm of the changing development patterns at home and abroad. If entrepreneurs can seize this opportunity and provide a suitable development environment for overseas students, they can not only promote the innovation and upgrading of their own enterprises but also drive a positive cycle of talent, technology, and culture, injecting new vitality into China’s innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem.